Draw With Jazza Art Sation

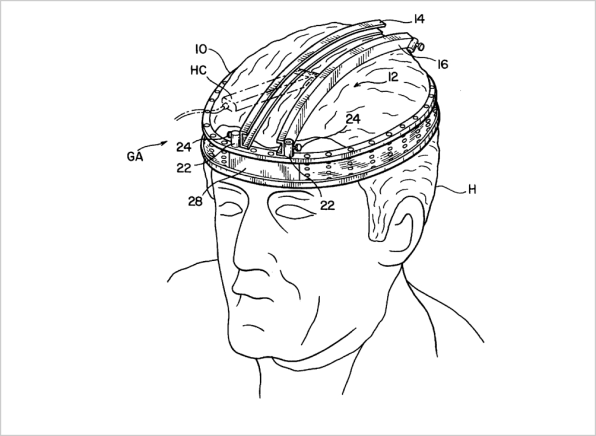

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, at 176 years old, has granted patents to some of the most important inventions in American history. It's also granted some of the dumbest (see: Patent 5,865,192 for a Self-Haircutting Guide Apparatus). All told, the office has approved more than 8 million patents (and rejected countless more).

At one time, patent applicants had to submit a physical model of their invention. Drawings were beautifully illustrated, full of colorful details. Today, the U.S. Patent office gives only cursory creative guidelines: no photographs, for example, though CAD drawings are fine. Drawings must be submitted on flexible white paper. And applicants are free to submit as many views as they want–though over-description has its risks. The idea is to describe your claim with as few lines as possible–similarly to an architect's construction details. The more unnecessary detail, the more likely a claim can be infringed upon or challenged.

As judge Richard Posner recently commented in The Atlantic, patent law is in something of a crisis these days. Patent litigation has exploded in the past two decades, increasing by more than 200% since 1990, around the time when "patent trolls" discovered they could buy up thousands of patents and sue alleged infringing parties for profit. And as litigation between tech giants like Apple and Samsung increases, many are asking whether America's intellectual property laws are in desperate need of reform.

Patent law, like all law, is a complex pressure valve, since it must satisfy two competing interests. On the one hand, it has to protect intellectual property–thereby protecting fair competition. On the other, it must protect innovation as a broader force in the market, which means allowing smaller companies to build on the successes of others. It's a careful balancing act–one that we'll continue to talk about as the patent wars escalate.

As patent law–and by proxy, patent art–edges its way into pop culture, we've found ourselves drawn to the U.S. Patent Office's cavernous database. Ten of our most interesting finds follow.

Patent 112,550: Creeping Baby Doll

This 1871 patent for a mechanical crawling doll was accompanied by a fairly terrifying working model. This was just six years before the 1877 U.S. Patent Office Fire, which destroyed 80,000 patented models. Soon after, the office did away with the model requirement.

Patent 1,475,024: Traffic Signal

Garrett Morgan, the African-American inventor of the smoke hood and the stop light, worked during an era some call the "golden age" of patent drawings. Morgan sold this 1923 design, for a stop light, to General Electric for $40,000. The drawings are carefully constructed hybrid views, mixing exploded axonometric views with shaded elevations and a keen eye for composition.

Patent 2,708,656: Neutronic Reactor

There are more than 8,500 patents by Manhattan Project scientists, all detailing the specifics of their quest to build an atomic bomb. It goes against all intuition that such a top secret project would be patented, but as NPR recently noted, the U.S. government had fears that their scientists might file their own patents in an attempt to control how the technology was used.

"What I really like about the atomic patents is that there is a wonderful banality to it. You really see it through the eyes of a patent lawyer," Harvard history of science student Alex Wellerstein told NPR.

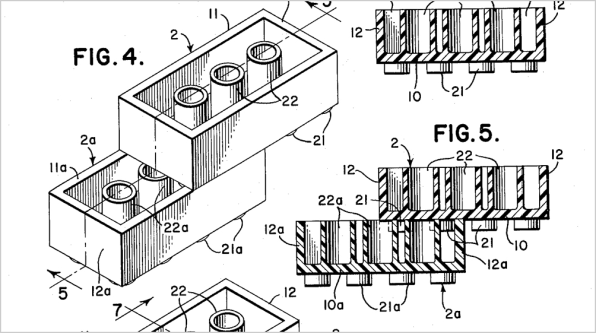

Patent 3,005,282: Toy Building Block

The original 1951 Lego patent (now expired) specifies every possible dimension on its simple plastic bricks and tiny yellow dudes. But the drawings themselves are unassuming lessons in axonometric simplicity. Elegant, serpentine call-out lines snake away from the Lego, pointing out details and measurements.

Patent 3,216,423: Apparatus for Facilitating the Birth of a Child by Centrifugal Force

Even the most horrifying patent can speak to the scientific fin de siecle of its time. This 1965 patent for a medieval-looking contraption, which spins a pregnant woman on a circular board until the child is "pulled out" from the force, was clearly inspired by NASA's human centrifuge training, which reached its pinnacle during the mid-'60s. John Glenn would later call it "sadistic."

Patent 3,197,927: Geodesic Structures

Buckminster Fuller patented his ideas and designs enthusiastically. This 1965 patent for the geodesic dome was actually a revised version of his original patent, from 1954. The geodesic dome relies on Fuller's concept of structural "tensegrity," a system of compression members held in place by a tension web. He patented that idea, too, in 1962.

Patent 4,344,424: An Anti-Eating Face Mask

"Obesity is a basic problem with which many people today are confronted," explain the applicants of this 1982 patent. While the U.S. patent database is bursting with misguided diet aids, this one is notable for its niche target demographic: restaurant workers. "When certain individuals are exposed to food constantly such as chefs, cooks, restaurant personnel or the like, it is a foregone conclusion that these individuals will consume far more food than is proper particularly when such food is usually readily available at no cost."

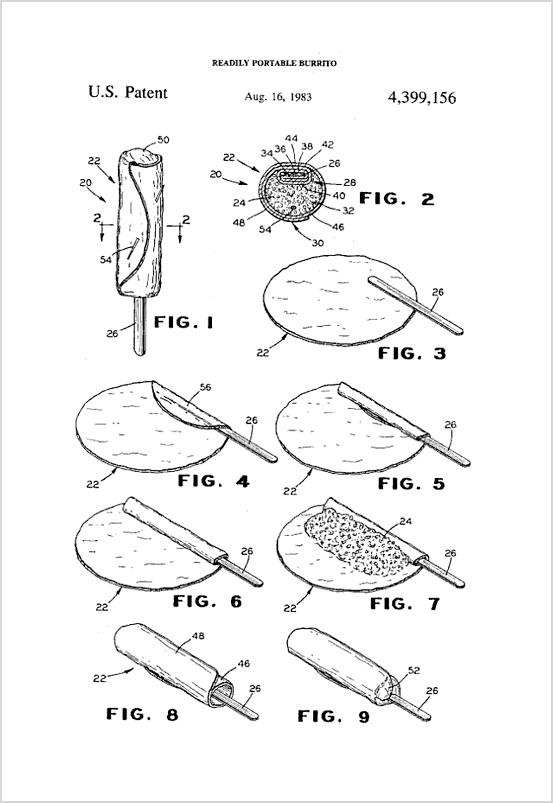

Patent 4,399,156: A Readily Portable Burrito

A patent for a "highly portable Mexican-type food item," registered only one year later, is proof positive for the Anti-Eating Face Mask. This application is notable for its multitude of drawings–among them, the excellent sectional view of a burrito you see here.

Patent 6,276,176: A Pantyhose Under Garment

The simplicity of the 1998 patent drawing for lady-shaping device Spanx is sweetly hilarious. It was drawn by the inventor's mother who, inexplicably, seemed to feel that a well-articulated toe would enhance the strength of the claim.

Patent 2,565,267: Bent Skyscraper

Patents that protect specific types of buildings are a recent and fairly controversial development. This application (via) from 2002 is only a joke, perpetrated by Rem Koolhaas in the pages of Content, but it's not far off from the reality of some architects. The faux-patent protects the formal shape of the CCTV tower in Beijing, described as a "method of avoiding the isolation of the traditional high rise by turning four segments into a loop." We can't help wondering what skyscrapers would look like today, had Mies van der Rohe protected his monolith-on-a-plinth scheme for the Seagram Building with a patent.

Patent 7,812,826: Portable Electronic Device with Multi-Touch Input

Today, patent artists must describe how humans behave with a technology, as well as the technology itself. One of Apple's thousands of patents, from 2006, specifies the details of their multi-touch interface. Apple's recent victory over Samsung focused largely on design details of the iPhone, with much attention paid to this and other drawings. What was fascinating about the trial–you can read a very entertaining play-by-play here–was that Apple's argument depended on some incredibly broad aspects of the design: the beveled edge, for example, or the pinch-to-zoom interface, specified here.

From Apple's perspective, the competition is piggybacking on the innovations they developed on their own. And certainly, judge and jury supported that claim. But some are questioning whether such aggressive legislation is actually hindering market innovation–e.g., forcing designers to purposefully differentiate themselves from Apple, even though Apple's solution may have been the best.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/1670762/the-unsung-art-of-patent-drawings

0 Response to "Draw With Jazza Art Sation"

Post a Comment